Open Source License Trends: 2017 vs. 2016

Table of Contents

Looking back at 2017, the year succeeded in serving us a healthy bit of open source licensing drama. How much drama, you ask?

The Facebook patenting clause, for example, swept many developers into endless message-board musings and assertions about the ins and outs of patent law. In the Linux community, Patrick McHardy, infamous Netfilter contributor, went rogue and decided to take GPL enforcement activities up a notch, taking quite a few companies to court over alleged GPL licensing violations — much to the dismay of Linux community leaders, who have always favored settling licensing issues outside of the courts.

Most developers don’t typically spend much time thinking about their project’s open source licensing, but when the legal issues start making headlines or spur extra long threads on reddit, we know that open source licensing and the threat of copyright or patent trolls are on our minds and not just behind the closed doors of our organization’s legal department’s meeting room.

Open source licenses in 2017: What’s hot and what’s not

To take a closer look at the ins and outs of open source licenses over the past year, our research team analyzed our database of over 3M open source components and 70M source files, covering over 20 programming languages, to see which open source licenses were most popular in 2017, in comparison to 2016. We found that results show a few very interesting trends in open source licenses. Here is our rundown of what’s hot and what’s not in the world of open source licenses.

“Anything goes”: The rise of permissive open source licenses

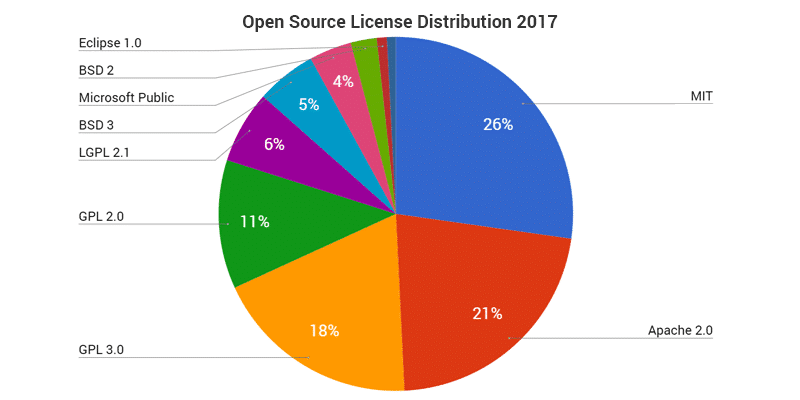

The first trend that we can see in the data is the continued rise of components with permissive open source licenses, with the permissive MIT and Apache 2.0 licenses leading the pack.

“Anything Goes”, otherwise known as permissive licenses, place minimal restrictions on what can be done with the code, allowing the freedom to use, modify, and redistribute it, and permitting its use in proprietary derivative works.

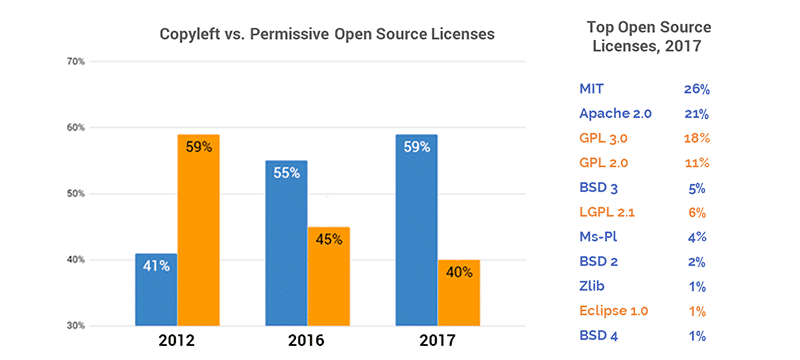

According to this year’s data, 59% of open source components have permissive licenses, compared to 40% components with copyleft licenses. The numbers have distinctly shifted towards permissive compared to last year — when the copyleft licenses held 45% of distribution compared to 55% permissive. This is particularly significant if we look at the situation five years ago, in 2012, when permissive licenses covered only 41% of open source components.

Ben Balter, product manager at GitHub, reflecting on the rise in use of permissive licenses, has said that the shift has a lot to do with the change in how developers see open source, and their priorities when developing open source projects: “There’s not the same friction with closed-source software that there once was, and as such developers often opt for practicality over purity. Developers contribute to open source because they want to build cool things, and they believe it’s the best (only?) way to build software. The philosophical motivations, although still underpinning their contributions, aren’t as in the forefront as they once were.”

The MIT open source license

The MIT license still reigns supreme as the most widely used open source license, supporting 26% of all components, one percent up from last years 25%. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, as it’s an old favorite in the open source developers community. According to Balter, nearly half of all licensed repositories on GitHub are opting for the MIT license because it’s an easy choice for developers, explaining that, “It’s short and to the point. It tells downstream users what they can’t do, it includes a copyright (authorship) notice, and it disclaims implied warranties (buyer beware). It’s clearly a license optimized for developers. You don’t need a law degree to understand it, and implementation is simple.”

GitHub’s choosealicense.com recommends the MIT license for developers that want a simple and permissive license for their project, simply stating that the license “lets people do anything they want with your code as long as they provide attribution back to you and don’t hold you liable.” Babel, NET Core, and Rails are a few of the popular projects that use the MIT license.

The MIT license and its easy usability came to Facebook’s rescue this past year to help put an end to Facebook React’s recent BSD + Patents license woes, following major backlash from the Apache Foundation and the development community. When Facebook replaced its unique and contentious open source license with the MIT license, everyone involved in the kerfuffle stood down.

Apache 2.0 license moves to the top

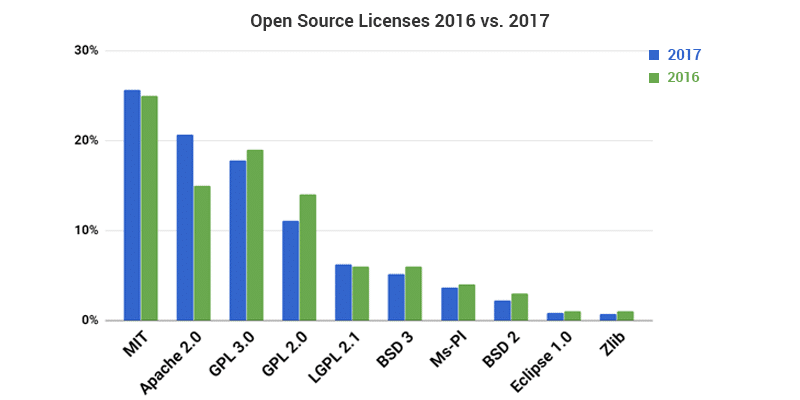

While the MIT open source license continues to lead the pack as it has for the past few years, Apache 2.0’s jump compared to last year’s results is big news. Last year, Apache 2.0 was found to be the third most common license in our open source components database, used by 15% of open source licensed components. This year, the permissive Apache 2.0 license moved up to second place, with an additional 6%, supporting a total of 21% of all components, replacing the popular copyleft GPL 3.0, which was kicked back to third place with 18%, one percent down from last year’s 19%.

GitHub’s chosealicense.com recommends the Apache 2.0 license for developers that are interested in a simple and permissive open source license, and also require it provide an express grant of patent rights from contributors to users. Like the MIT and other permissive open source licenses, Apache 2.0 allows licensed works, modifications, and larger works to be distributed under different terms and without source code. A few popular projects using the Apache 2.0 license are Elasticsearch, Kubernetes, and Swift.

GNU GPL family open source licenses: Still going strong

While the popularity of “Anything Goes” licenses is evident in the data, we shouldn’t ignore the rest of the numbers. GNU GPL family of licenses, which includes GPLv3, GPLv2, and LGPLv2, is still going strong as the most used family of licenses out there, with 35% of all open source components using a GNU GPL version. This family of licenses comes from a large and strong open source community — GPLv2 is the Linux license — and it’s not going anywhere.

The GPL is a copyleft, or viral license. This means no matter how many or how few of the components in your code are GPL, you are required to release its source code, as well as the rights to modify and distribute the entire code. Furthermore, you must also release the source code under the same GPL license (hence the name viral license).

However, being such a strict license, quite a few points of debate arise. How much of your software do you need to release as open source under the GPL license. The GPL v2 requires you to share the code of all “derivative work” from the project. Yet what exactly does the term “derivative work” mean? It appears some companies, and patent trolls, choose to interpret this term more loosely than others.

Community leaders, including open source OG Linus Torvalds, have voiced their concern over GPL enforcement, and some giants and leaders have begun to address these issues. A few actions have been taken over the last year in attempt to help companies along with GPL compliance and reign in the patent trolls. Facebook, Red Hat, IBM, and Google committed themselves to “providing a fair cure period to correct open source GPLv2” compliance issues,” in an attempt to bring companies that are developing incorrectly with the more restrictive code in from the cold without penalty.

In response to a rogue Linux community developer filing multiple lawsuits for GPL enforcement against Linux distributors, the Software Freedom Conservancy issued a set of guidelines for how to encourage community enforcement of standards for working with licenses. The Linux community, on their part, also published a statement, to be included in all future Linux documentation, addressing “ambiguities” in the GPL 2.0 license, to be included in all future Linux documentation.

Open source licensing moving forward

One good thing about the legal back and forths that have caught our attention over the past year is that they are ongoing reminders for us to mind our open source licensing practices.

The open source community is most often inclined to encourage license compliance without litigation, outside of the courtroom. As more organizations contribute to the open source development community, they are also intent on encouraging compliant open source usage — meaning helping companies to get friendly with their open source licenses and stay compliant.

So as long as you mind your GPL’s and keep your MIT’s crossed — you’re sure to stay out of the crosshairs of anyone’s legal team.

We have a newer post about open source license trends and predictions.